Human Resources Officers

Chief people officer of 2030: Building a tool kit to get from here to there

HR leaders are well into an evolution of their roles, from back-office operational specialists to full strategic partners. They are grappling with transformation in ways large and small every day—in their role, in their function, in their organization, and in the wider world. The Covid-19 pandemic kick-started the pace of change, but volatility since, including geopolitical and economic volatility, new workforce expectations, new stakeholder expectations, and step changes in digital tools—most notably AI—means that change hasn’t slowed. Chief people officers (CPOs) are having to reinvent both themselves and their functions in real time.

This evolution has created an inherent tension in HR. The function is still responsible for foundational operations related to people, such as making sure employees are paid properly and on time, extending benefits, and negotiating labor contracts. But it is also responsible for attracting, developing, promoting, and retaining game-changing talent; making sure the right talent is in the right places; ensuring the organizational design makes sense; and supporting a thriving culture, to name just a few of its remits.

Neither CPOs nor CEOs and board members are satisfied with where things stand. Our discussions with more than 50 CPOs at Fortune 500 and FTSE 350 companies highlighted five key challenges:

- Building the capabilities and capacity, individually and in the HR function, to take on the new strategic mandate

- Developing the perspective and agility to manage the leadership pipeline and workforce in the context of shifting strategic goals

- Navigating change, innovation, and stability in a cost-constrained environment

- Addressing generational and workforce megatrends

- Mastering AI, technology, and data-driven decision making

CPOs need a new tool kit to transform themselves and their function in the context of their transforming organizations. Further insights from these discussions, combined with our research and ongoing conversations with additional CPOs around the world, suggest three focus areas for CPOs to build the expertise, relationships, and function needed to thrive in 2030: delivering impact with leadership liquidity and a dynamic workforce; channeling innovation and enhanced productivity with AI; and fostering resilience and inclusion.

The key challenges for CPOs today

CPOs have indicated five challenges reshaping their role and responsibilities. By deftly addressing these challenges, CPOs can ensure organizations better support their leaders and are prepared for the future.

- Building the capabilities and capacity to meet the new strategic mandate

- Developing the perspective and agility to manage the leadership pipeline and workforce

- Navigating change, innovation, and stability in a cost-constrained environment

- Adjusting to generational and workforce trends

- Mastering AI, technology, and data-driven decision making

CPOs are often key strategic partners within the executive leadership team. We see that companies increasingly want a CPO who can consider, and transform when needed, the organization’s design, its leadership, and its people strategy in response to the company’s particular situation as it changes over time—leaders who build for the business, not for HR alone. The shift in the title, from CHRO to CPO, in many organizations underscores the degree of change in the HR function and the broader strategic remit of these leaders.1 This shift in the role is also leading to the evolution of the HR function because the function needs to support the CPO differently.

Because so much is net new and many changes are affecting the entire enterprise, CPOs today must be systems thinkers; competently executing the responsibilities of the HR function is no longer nearly enough. The organizations winning in 2030 will have CPOs who are true business leaders, who shape the top line versus focusing on traditional bottom-line management. This requires CPOs to get deep into strategic conversations—on workforce planning, talent attraction, development, and retention, succession planning, and business outcomes—all while navigating generational shifts and leadership dynamics. In this rapidly evolving talent landscape, they must lay out future workforce plans that take into account location strategies, cost–benefit analyses, skills-based hiring, and contingent labor.

CPOs must be at the heart of the overall company agenda and build high-value, influencer relationships across the executive team, including an elevated relationship with the CEO. Many CPOs are partway there, striving for stronger, more productive partnerships, but they are not always finding the most-senior leaders open to meaningful debate and dialogue. That said, CPOs do often indicate that they are finding key co-strategists in the CEO’s direct reports and division leaders.

As the CPO spends more time on strategic matters, other leaders within the function need to step up on the traditional HR operations side. The function must drive short- and medium-term development plans for the organization, as status quo is not an option. Some do this by establishing a program office to manage multiple projects.

In addition, CPOs must ensure that they themselves and other functional leaders develop their knowledge about emerging opportunities, risks, and technologies to maintain high performance. Many HR functions also need to shift the balance of their employees toward people with strong digital skill sets as data and AI play a larger role in HR operations, and HR analytics must shift toward predictive analytics skills to be useful in CEO decision making.

Last, but not least, the new strategic mandate will also require CPOs and other functional leaders to tackle tasks such as reevaluating sustainability and DEI approaches. These conversations are evolving, with companies becoming more selective in the issues they address publicly. Balancing external pressures and internal cultural values remains a challenge.

With CPOs having a more strategic role, they have greater insight into, and influence and impact on, the company’s ability to reach its goals. This means taking a longer-term perspective than ever before—but also one that is able to change rapidly in response to strategic and market shifts. It requires a deep understanding of how to respond to changes in talent markets, the need for reskilling, the potential of more fluid labor markets, and the options for organizational redesign. It also requires the ability to treat the company’s leadership pipeline holistically and as a long-term strategic asset, rather than the traditional model of siloing functions such as executive attraction, retention, development, and succession planning.

This last point is a particular pain point—not only for CPOs but also for CEOs and board members. According to a recent Heidrick & Struggles survey, CEOs and boards of more than a third of companies around the world have low confidence in their organization’s ability to meet its strategic goals. These leaders particularly lack confidence in their executive succession and leadership planning: nearly half aren’t confident those processes are positioning their organization well for the future.2 Many executives at other levels have pointed to failures of connection between individual leader development and succession planning as a particular problem.3

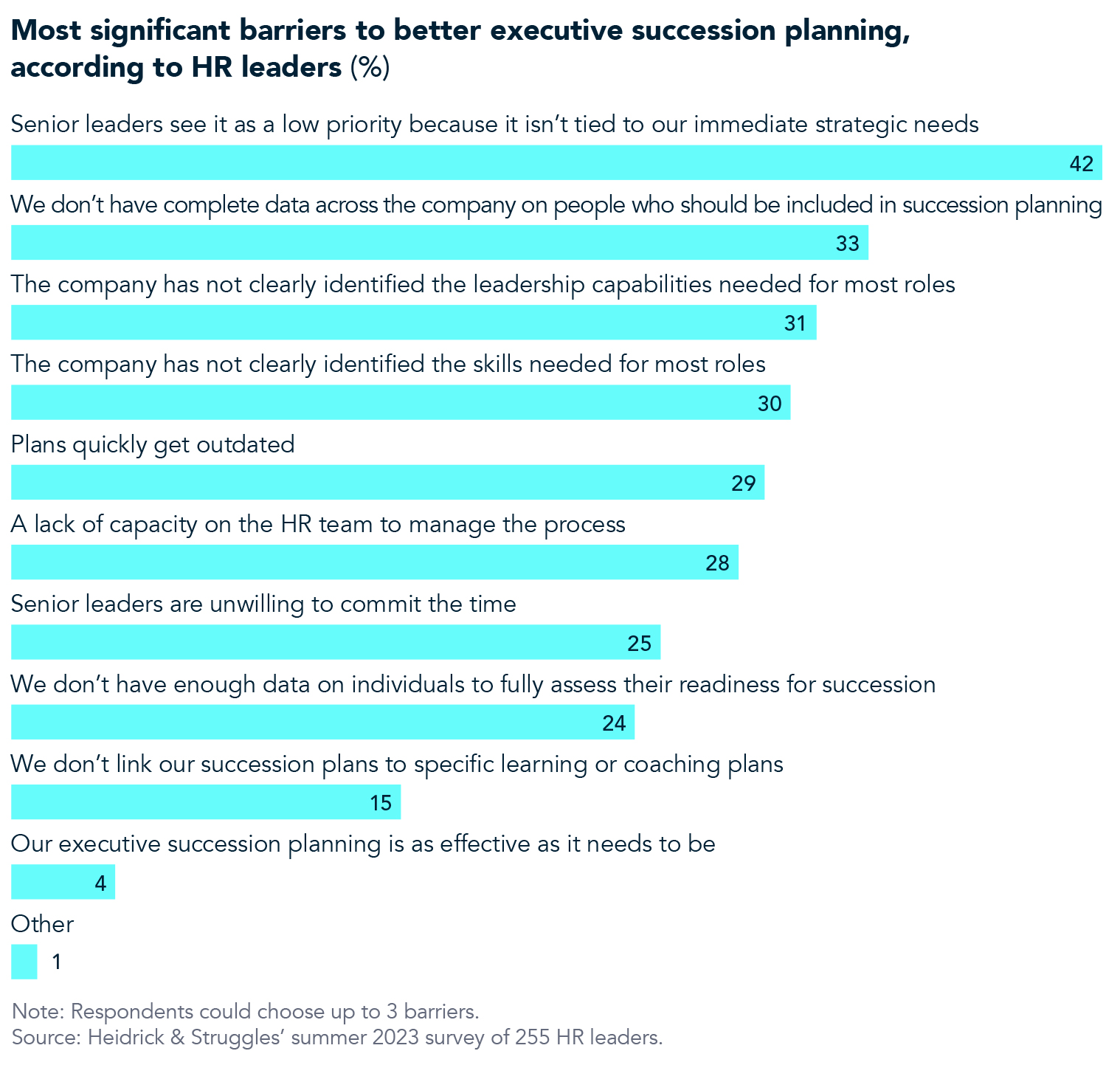

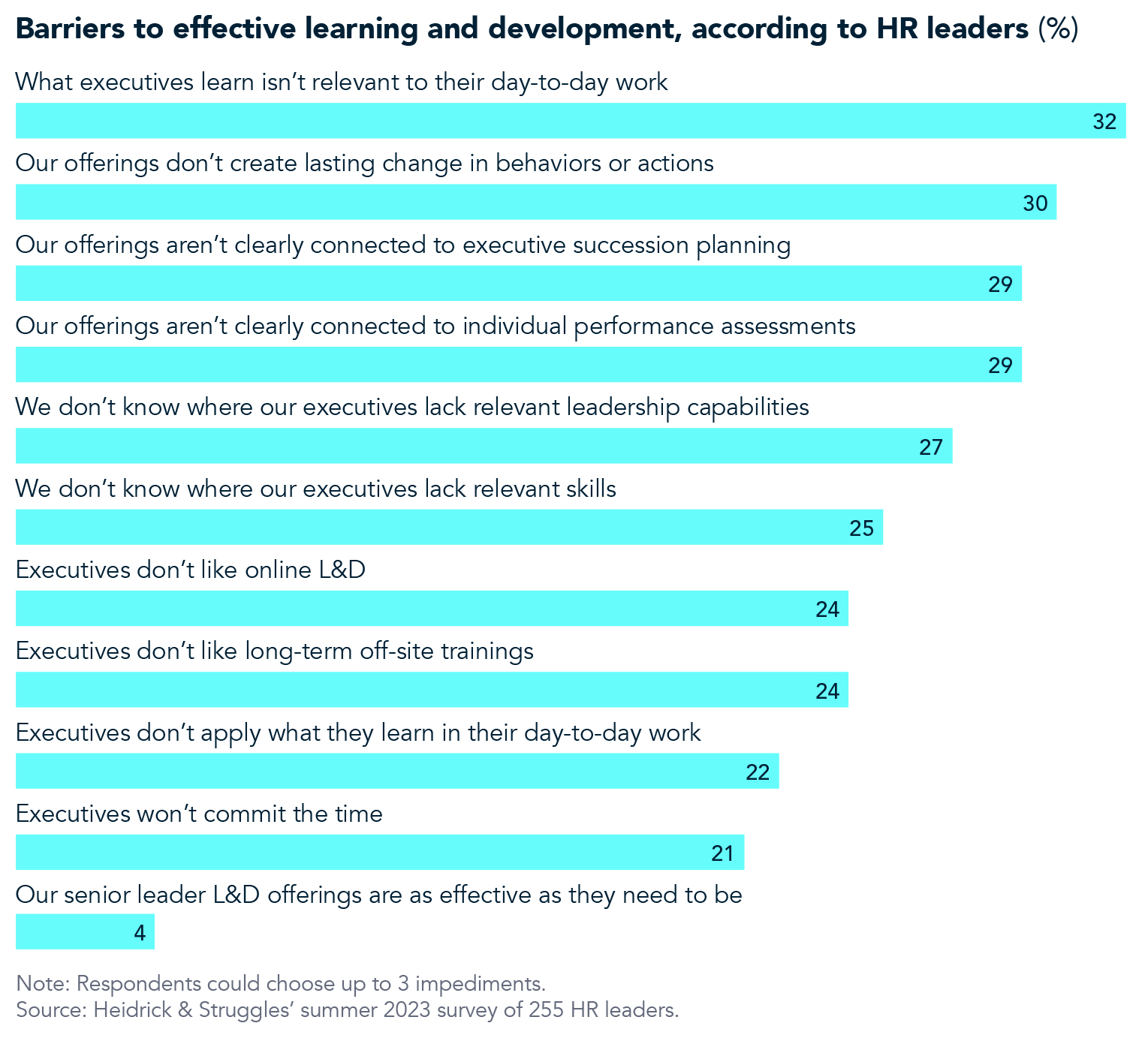

In another survey, CPOs cited several significant barriers to improving executive succession planning, and just 4% said their executive succession planning is as effective as it needs to be. CPOs also cite failures in their leadership development programs.4

Executives’ number one suggestion for improving promotion and succession planning processes is linking these processes more closely to individual executive learning and development plans.5 But if doing that were straightforward, CPOs would have made the changes already.

Another area where traditional structures and practices are inhibiting transformation is in benefiting from more fluid labor markets at every level. In a rapidly changing environment, where new skills can be required for leaders and the whole workforce with little notice—such as the sudden emergence of gen AI two years ago—interim employees can be a significant part of the solution. But in most cases, this kind of hiring resides in procurement or within functional lines of business, which disrupts planning and budgeting for fractional and project-based workers.

CPOs are tasked with guiding the workforce through transitions, including technological advancements such as AI to reinvent the employee experience, while maintaining employee well-being and preventing burnout. This includes fostering adaptability and building resilient leadership pipelines for the future, all in a cost-constrained environment. As one CPO said recently, “Every year we have less and are asked to do more.”

At the beginning of Covid, it seemed that the need to find this kind of balance might be temporary. It is clear now that it is persistent, as organizations learn to live with volatility in an era of “permacrisis.” Wars, climate crises, and political upheaval are near constant, and their effects are felt within businesses—for example, in terms of employee mobility, cross-national teaming, and engagement. CPOs face an urgent question of how they can bring a workforce together when more and more people won’t even talk to one another.

This reality requires CPOs to provide more simplicity and clarity than ever, so people can focus on what’s in front of them and keep executing. There is no single approach to supporting people and the business during volatility; each situation requires adaptability, instinct, and cultural sensitivity, particularly with a globally diverse workforce. CPOs should balance empathy and neutrality, offering support while maintaining focus on business objectives.

Navigating all this is requiring CPOs and the HR function to evolve their traditional models and methods in these areas as well, which is something many still struggle with.6

Shifts in workforce demographics—including the rise of Gen Z, remote and hybrid work preferences, and the growing use of on-demand experts and gig workers—all require CPOs to adapt engagement, retention, and talent management strategies.

CPOs have to address the demands of younger workers while not alienating older generations, though our discussions suggest that this often-cited concern may be somewhat overblown. For example, we heard from one CPO that Gen Z workers demanded an on-site therapist, who was then used by employees of all generations. So it may well be that all workers can benefit from some of the expectations of younger workers in other ways as well. Then there is the larger issue of navigating the balance between in-office expectations and workforce preferences for remote work. While younger employees value in-person mentorship, some, particularly parents of young children and people with physical disabilities, prioritize the flexibility and convenience afforded by hybrid or remote working arrangements.

More broadly, more and more employees at all levels, including leadership, prefer to work outside traditional career norms. For example, we see many data scientists and digital innovators preferring to take contract roles and move rapidly from organization to organization to keep their skills fresh.

Furthermore, the expectations of people who do pursue employment at a single company are also challenging traditional approaches. Gen Z’s focus on gaining skills and prioritizing purpose over long-term job security (sometimes referred to as “purpose over pension”), for example, is causing organizations to rethink engagement and retention strategies in a context where, our research has shown, development and promotion opportunities are an important tool. Younger workers are also demanding meaningful work opportunities and career paths that are individualized; already the phrase “mass individualization” is becoming familiar. So, as skill development becomes more important, leaders are seeing a trend toward in-office work for growth and collaboration, which still needs to be balanced with the other benefits workers see in remote options.

Another trend is that the number of Gen X leaders in the workforce will not be sufficient to keep pace with the rate at which leaders in previous generations are leaving their roles—the youngest Baby Boomers will turn 65 in 2030. This is opening up opportunities for Millennial executives to make up a much larger proportion of leadership pipelines at earlier ages than previous generations. CPOs should be focused on this group’s developmental needs to ensure they will be ready for executive roles.

CPOs have to address these trends and shifts and support leaders as they do the same, leading with more care, compassion, and kindness than ever before and with a heightened focus on building resilience and bench strength in the workforce.

AI and other emerging technologies are becoming embedded across functions, revolutionizing work, productivity, and decision making. Most leaders say AI is being used in at least some parts of their organizations, but 51% of all leaders (and 54% of HR leaders) say they’re not adopting it fast enough. The top barrier to progress is talent, as it’s hard for companies to find the AI expertise they need.7

It’s not yet clear how emerging technologies will fundamentally shift the HR agenda. But whether it’s the same job, a new context, or a role transformed altogether, what is clear is that the people function’s ability to use available technology—and to support the entire organization in learning to use it—must improve.

Across the organization, CPOs need to support other leaders in leveraging AI effectively while managing its risks, such as potential workforce displacement and the need for retraining. HR leaders are perhaps more aware than many other executives that, at most companies today, AI is advancing in small steps, affecting specific processes but not causing wholesale changes in the workforce—yet. Nonetheless, AI can already create significant amounts of change, and CPOs must be able to advise on the best ways to deploy the human time that AI adoption can free up. One CPO, for example, found that when their organization introduced new AI tools, it saw a 15% increase in productivity—which immediately raised the question of what to do with that time.

In addition, job and organization design require a deep understanding of the technology, so it’s now a requirement that the HR function be literate in the capabilities of AI, big data, and large language models. CPOs must get crystal clear on the strategic rationale for adopting—or not adopting—these tools and then stay ruthlessly focused as technologies and strategies evolve and as companies find the compelling business cases for wider implementation of AI.

Getting from today to 2030

Most of these challenges for CPOs are inherently cross-functional, and, as we have noted, the traditional HR tool kit doesn’t work well to address them. CPOs know they need to fundamentally disrupt their function in order to help it, and the entire organization, transform to thrive. They are already beginning by developing their own and the function’s knowledge of and connections to the business, which is also helping change mindsets across the organization about what HR can do. But there are three other key ways CPOs can pursue transformation.

Driving impact with leadership liquidity and a dynamic workforce

Finding ways to create a more dynamic employment model, in response both to workers’ new expectations and to more variable strategic needs, is central to meeting many of these challenges. One core concept we see some CPOs using is “leadership liquidity,” in two distinct areas: developing leaders who are curious, agile, and eager to learn and drive innovation; and developing leadership teams that are dynamic in terms of their composition and the expertise and capabilities represented on them. One important approach for leadership development is assessing leaders for these capabilities, helping leaders develop them, and ensuring leaders have opportunities to take cross-functional roles in various parts of the organization.

As we have noted, one specific helpful tactic is making more use of interim executives and project managers across the organization. Not only can these specialists lend expertise or fill short-term gaps, but they can also pilot new roles and help companies determine the most effective capabilities for the longer term. But to do so, many CPOs will need to change hiring policies and practices developed for a more static age. These approaches will also require CPOs to rethink how leaders with these kinds of roles become, and stay, connected to the business.

Another, more foundational, change is to ensure that the internal leadership pipeline is treated as a strategic asset. Many CPOs have felt stymied by the persistence of hybrid work models, particularly since large numbers of senior leaders have felt these models were disrupting the development of more junior executives. Research we have conducted has found that, in fact, what executives think is most effective for leadership development varies very little between hybrid and fully in-person work models.8 So CPOs should seize the opportunity to make the changes they think will work best for their organizations in the long term to integrate the silos of attraction, retention, development, promotion, and succession planning, and align them with strategic planning.9 Most will also benefit from extending succession planning far deeper into the organization than they do today.

Data will also be a valuable resource for CPOs looking to fully understand their leadership bench and maximize impact. Most companies make far too little use of the assessments they regularly conduct of their leaders and other employees, for example. They can use that data—even more effectively with AI support—to improve all kinds of processes related to people, including executive attraction, retention, development, and promotion and succession strategies.10 This in turn can improve workforce planning, executive retention, and team dynamics—and, likely, strategic impact.

Often, HR leaders who have been through the implementation of HR information systems and workforce management software aren’t eager for more new tools or technologies. Nonetheless, we expect the sweeping changes AI is bringing to the preexisting shift toward data-driven decision making to make change inevitable, and CPOs who are early adopters may well be able to create a lasting competitive edge.

Channeling innovation and enhanced productivity with AI

CPOs have a leading role to play in helping their companies answer some fundamental questions regarding AI: whether to embrace a bottom-up approach or to impose a top-down approach to implementation; how roles will change in response to the support AI offers and how to reshape the organization in response;11 and how to upskill the workforce. In addition, like all other functional leaders, they can use AI to do routine work and free up people to do more strategic work. This will not only make the function more productive but also help address stress and burnout across the function.

As HR is asked to do more with less, CPOs should consider where AI can help the most. One CPO said, “Knowing it’s always there running in the background, how do we use that to make jobs more human and take away burden and burnout?” Our research suggests AI could play a significant role in talent assessment, employee engagement, risk assessment, bias identification, rewards, HRIS, and organizational design—disrupting the function’s traditional work models to increase productivity. Looking ahead, HR leaders most often expect to be using AI for workforce planning, HRIS overall, total rewards, aggregating employee feedback for performance reviews, recruitment scheduling, and understanding workforce trends.12 Some HR functions are already deploying chatbots as digital agents to automate low-level administrative tasks, allowing HR business partners to focus on relationships with business leaders and future-focused initiatives. Employee surveys and listening programs are being synthesized by AI to provide real-time insights. And in recruiting, automated scheduling and meeting transcriptions are reducing the administrative burden.

We have seen some progressive CPOs taking the opportunity of AI experimentation in the HR function to learn enough to be very effective advisers to other functions on AI adoption as well as the workforce implications. That said, there is a delicate balance between pursuing innovation and maintaining stability in an organization; constant change, while necessary, must be sustainable to avoid overwhelming the workforce.

Fostering resilience and inclusion

Resilience is crucial to thriving through transformations, large or small. Maintaining it has always been difficult, and as uncertainty, exhaustion, and divisions among workers, consumers, and leaders in many regions become more prominent, it can be more difficult to maintain now than ever before. Divisions matter because inclusion, feeling like we are all in it together, is a key element of resilience. Leaders know this: they generally agree that the ability to lead across the boundaries and divides most important to their workforce and in their key markets influences their organization’s ability to achieve its goals; 46% of CEOs and board members in the United States, for example, said in a recent survey that this ability was foundational.13

CPOs need to encourage healthy dialogue at all levels of the organization to build inclusion and resilience so teams can act as a unified force. Almost all CPOs are also expanding programs to support employee health and wellness and exploring other benefits specific to their workforce’s interests, to bolster resilience across the workforce.14

For leaders at all levels, many CPOs see fostering growth, development, and engagement as important to resilience. Our research suggests that transparency about opportunities is an important element of fostering a sense of growth and connection. Resilience and inclusion can be particularly complex on the executive team. At this level, CPOs are often the glue: they advise the CEO, of course, individually and on team dynamics, and they often also act as formal or informal mentors to other C-suite leaders.

***

It is a time of transformation for CPOs and the broader HR function. Finding the right ways for their organizations to embrace a dynamic workforce, make the most of AI, and build resilience will help CPOs navigate the challenges of today and tomorrow and supercharge their strategic effectiveness.

We look forward to continuing this discussion with you.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Maria Konat, Kirsty Osborne, and Elizabeth Real for their contributions to this article.

About the authors

Darren Ashby (darren.ashby@businessfourzero.com) is the chief impact officer and partner at businessfourzero, a Heidrick & Struggles company; he is based in the London office.

Emma Burrows (eburrows@heidrick.com) is the regional head of the Human Resources Officers Practice in Europe and Africa and a member of the CEO & Board of Directors Practice; she is based in the Brussels office.

Sandra Pinnavaia (spinnavaia@heidrick.com) is the global head of strategy and innovation for on-demand talent and leads the product innovation team at Business Talent Group (BTG), a Heidrick & Struggles company; she is based in the New York office.

Sharon Sands (ssands@heidrick.com) is the leader of Leadership Assessment, Development, and Coaching for Heidrick Consulting and co-leader of the CEO & Board of Directors Practice in the United Kingdom; she is based in the London office.

Brad Warga (bwarga@heidrick.com) is the global co-head of the Human Resources Officers Practice; he is based in the San Francisco office.

Jennifer Wilson (jwilson@heidrick.com) is the global co-head of the Human Resources Officers Practice; she is based in the Dallas office.

References

1 For more on this evolution, see Steven Krupp, Brad Warga, and Jennifer Wilson, “The next evolution of HR leadership: The connecting HR leader,” Heidrick & Struggles, September 19, 2024, heidrick.com.

2 “CEO and board confidence monitor 2025: Persistent concerns, pockets of increased confidence,” Heidrick & Struggles, February 5, 2025, heidrick.com.

3 Heidrick & Struggles proprietary research.

4 Heidrick & Struggles’ summer 2023 survey of 255 HR leaders.

5 Heidrick & Struggles proprietary research.

6 To gain more in-depth insights on barriers to change and how some HR leaders are innovating, see Steven Krupp, Brad Warga, and Jennifer Wilson, "The next evolution of HR leadership: The connecting HR leader,” Heidrick & Struggles, September 19, 2024, heidrick.com.

7 Victoria Reese, “What AI could mean for talent across the C-suite,” Heidrick & Struggles, heidrick.com.

8 Heidrick & Struggles proprietary research.

9 For more on how some companies are beginning to do this work, see our articles on readying leaders for the future on heidrick.com.

10 For more, see Sarah Arnot, Sharon Sands, and Todd Taylor, “Treating your leadership pipeline as a strategic asset: How data can improve every aspect of executive leadership development and succession planning,” Heidrick & Struggles, July 31, 2024, heidrick.com.

11 For more on how leaders can think about organizing for AI, see Ryan Bulkoski and Adam Howe, “Structuring the AI function: The right questions to find the right model,” Heidrick & Struggles, November 14, 2024, heidrick.com.

12 “How HR leaders are using AI today,” Heidrick & Struggles, 2024, heidrick.com.

13 For more on leaders’ perspectives on leading across boundaries and divides, see Jeremy C. Hanson and Jonathan McBride, “Leading across boundaries and divides,” Heidrick & Struggles, November 8, 2024, heidrick.com.

14 For more on CPOs and wellness, see Emma Burrows, Sharon Sands, Brad Warga, and Jennifer Wilson, “Chief people officers in focus: What new HR leaders need to know,” Heidrick & Struggles, October 24, 2024, heidrick.com.