Chief Executive Officer

Too aware to fail

✔ Selling short on self-awareness

✔ Self-awareness—leaders’ greatest instrument for transformation

✔ Common leadership blind spots

✔ Why blind spots remain elusive

✔ Seeing blind spots and exercising the courage to manage them

Selling short on self-awareness

The son of a prominent New York family, the chair and CEO of Lehman Brothers, Richard Severin Fuld, ascended to the heights of his profession—a Wall Street lord and power player in global financial markets. Somewhere along the way, however, he lost his sight.

Like other investment bank bosses in the early 2000s, Dick Fuld salivated for years over the prospects of enormous fees and profits from repackaging America’s mortgages into securities. Ignoring warnings that the US housing market was on the verge of collapse and that mortgage bankers were issuing loans to consumers who could never repay them, Fuld instead hurried headlong into this new venture. To get ahead, the hyper-competitive Fuld led Lehman into more risk, pumping up more debt: prior to its 2008 collapse, the bank held less than a dollar in reserves for every $30 of its liabilities.

Despite the risk Fuld created for the bank, there was still a way out. According to Larry McDonald, a former Lehman vice president, Fuld was warned time and again to remove the blinders. There were at least three times that Dick Fuld and his president, Joe Gregory, were counseled by the “cleverest financial brains on Wall Street” to steer the banking Titanic around the colossal financial iceberg just ahead, going way back to 2005: “Dick and Joe turned their backs all three times,” wrote McDonald. “It was probably the worst triple since St. Peter denied Christ.”1

Fuld remained oblivious. And outside of Lehman’s obsession with sub-prime mortgages, the overall business was sound and profitable. As McDonald explained, the failure of Lehman Brothers, with 25,000 employees, came down to one simple fact: “It's 24,992 people striving hard, making money, and about eight guys losing it.”2

The Great Recession that followed Lehman’s collapse destroyed $8 trillion in shareholder value between 2007 and 2009. In the greatest and most abrupt wreckage of wealth since the Great Depression, Americans lost almost $10 trillion as home values plummeted and retirement accounts vaporized.3 That the Lehman bankruptcy led to one of the most destructive global financial collapses in human history is “old news.” But is it?

Its leadership lessons remain relevant today for anyone in charge. Or, as David Gergen, citing Bill George of the Harvard Business School, wrote, the economic crisis was “less a matter of sub-prime mortgages than sub-prime leadership.”4 What happened? Margaret Heffernan, author of Willful Blindness, observed that Fuld became cut off from reality:

“When CEO of Lehman Brothers, Richard Fuld was driven from his home to a heliport, then helicoptered into Manhattan, driven in another limo to the bank’s offices where a private elevator sent him up to his office. This ornate commute ensconced him in a physical bubble that no weak signals or accidental encounters could penetrate. This physical manifestation of power may look like luxury, but it comes at a cost. The bubble of power seals off bad news, inconvenient detail, hostile opinion, and messy reality, leaving leaders free to inhale the rarefied air of pure abstraction. Like the cave dwellers of Plato’s parable, the powerful risk mistaking shadows for reality.”5

A former executive who worked directly for Fuld during the time of Lehman’s collapse confided to me that his former boss was blinded to his own sense of superiority and infallibility: “He was exceptional in many ways but couldn’t see where he was less exceptional.”

Fuld would later take “full responsibility”6 for the decisions he made, but he also said he would not have done anything differently. Instead, he blamed “rumors, speculation, misunderstandings, and factual errors”7 for the bank’s failures and went so far as to justify the collapse as the result of a “perfect storm.”8

We should not minimize the complexity of the contributing factors of the Great Recession. But failing to acknowledge the unmistakable systems failure in leadership is putting our heads in the sand. It also prevents the kind of after-action leadership review that would mitigate financial collapses in the future.

Jamie Dimon, the legendary CEO of JPMorgan Chase, cemented his reputation in the way he navigated through the financial crisis of 2008. His cautious approach to risk and his laser focus on balance sheet flexibility indisputably helped him and the bank weather the storm. But there was something else. Highly aware of his own strengths and weaknesses, Jamie told me that “self-awareness” is a fundamental principle in leadership—but there must be more. You must leverage your awareness, he said, to have the courage of your convictions, to be decisive, to invest in talent, and to accelerate performance. Jamie reminded me of the military motto, “observe, orient, decide, act,” known as the OODA loop, a decision-making model developed by military strategist and United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd. Jamie explained that the “orient” part is all about the importance of self-awareness in the top job.

Famous for his annual “Heartland” road trips and his “open door” policy at JPMorgan Chase, these measures have allowed Jamie to mitigate against the structural bubbles of power that many CEOs tend to construct around themselves. Steely yet vulnerable, Jamie remembered one of the most defining moments that shaped his leadership journey, a moment that heightened his awareness and enabled him to show up as the better version of himself. And it didn’t take place at the office. Rather, it took place at home, when his kids were still young.

One day, Jamie was at home, on the phone with one of his colleagues. Jamie acknowledged the harsh tone in his voice on the call when his middle child started crying in the background. “Dad, why are you so angry at them?” An epiphany, Jamie told me, “that was a powerful moment for me.” It reminded him that people are wired differently and take things differently, and that one must be sensitive to these differences. “My job is to make my people feel trusted, respected, and valued,” he said. An intensified awareness, a brave vulnerability, the ability to adjust, and the prevention of a protective bubble around him has all undoubtedly contributed to Jamie Dimon’s success as the longest-tenured global big bank CEO and a titan of Wall Street.

Leaders who fail to dig deep to identify their own blind spots and wage war on them are bound to repeat the sins of the past and may fall short in mitigating the temptations that inevitably lie ahead. Leaders who make the effort to see and contend with those flaws may become almost too aware to fail.

Self-awareness—leaders’ greatest instrument for transformation

At Heidrick & Struggles, we believe leaders should always aspire to become the best versions of themselves. This can include both leading well wherever they are uniquely placed or reaching the top job of a respected function or organization. But, although every leader wants to be known for their achievements, most are too afraid to be fully seen as themselves.

A Japanese proverb says we all have three faces: the first face, you show to the world; the second face, you show to your close friends and family; and the third face, you never show anyone—but it is the truest reflection of who you are. As leaders, it is that third face we often neglect or refuse to get acquainted with, and doing so is what would enhance our awareness and accelerate our leadership.

That’s because what most often hinders us from reaching our full potential as leaders are internal impediments, not external ones. This is not to minimize the effects of discrimination or the fact that some leaders start with the advantages of wealth or family that help them get ahead. But all leaders struggle to balance an external focus on accomplishments and an internal focus on consistency and inner strength. Those who go with their better angels—who emphasize examining their leadership and seeking to improve it—rise above the rest. More fully: A heightened self-awareness of blind spots combined with the courage to combat those flaws will make a leader and their organization. A lack will break them.

Self-awareness is the greatest instrument for transformation that leaders have in their tool kits. It is the first piece of the one thing found missing in the leaders who led us into the Great Recession and other corporate disasters. Combating our flaws with courage is the other. Combined, these accelerate a leader’s journey to the top of their game.

Self-aware leaders understand that the very purpose of leadership is to place the interests of others ahead of their own, especially those who follow. They seek to make others feel seen and valued, or what we might call the “Ted Lasso effect.” The Apple TV+ show’s smashing popularity underscores a kind of societal yearning for the kind of leaders in urgent demand in today’s organizations—the benevolent coach who leads with empathy, kindness, and compassion. He recognizes that his players are human beings, not simply tools to advance his self-interest.

Ken Olsen, who co-founded Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in 1957, was such a leader. Early in his career, Olsen was known to be brutal and tyrannical at times and deeply disconnected from his team. Like Bill Gates, who called Olsen one of his heroes and who himself also acknowledged practicing an autocratic style early in his career, Olsen became aware of his blind spot and sought to overcome it. He created a non-hierarchal organizational structure unique at the time. An important part of this was that he started to wander around the office, stopping by, for example, an engineer’s desk and humbly asking, “What are you working on?” Since he was genuinely interested, he found himself in long conversations with engineers and others. The result, as one author put it, was that “even when the company had over 100,000 people worldwide, Ken was well known and loved because so many people had experienced him as a humble inquirer.”9

Leaders’ blind spots can be clear negatives, as with Fuld. But they can also be positive traits taken too far. Elon Musk, one of the greatest innovators of our time, acknowledged one of his inner flaws that may prevent him from achieving his audacious goals for humanity. A rare admission, perhaps, but Musk conceded, “It’s time you knew ... I’m sometimes a little optimistic about timeframes.”10 Optimism is an asset for any leader, especially in innovating and launching new companies. A strength overused, however, can turn into what we call a “derailer.” Musk’s intense performance standards for his people could be unsustainable or even disastrous. It may lead to biting off more than he can chew, which may be equally devastating. But he is aware of it, and, with some vulnerability, he put it out there.

Or consider Warren Buffett, perhaps the most successful investor of the last century, who identified his flaw as being too loyal. He lamented being too slow to make personnel changes over the years and cutting underperforming managers loose.11 Empowering managers with maximum autonomy has served the “Oracle from Omaha” well, but, overused, it too can derail. Buffett’s own self-awareness, and humility, has clearly accelerated his success as one of America’s legendary business leaders.

And there are many blind spots less dramatic than Fuld’s that hamper leaders every day—and that they can combat to transform their leadership and their organizations. For example, when I was advising Dan, the CEO of a global $10 billion public energy company, he lamented a certain shyness and introversion that kept him from connecting with his team. That, in turn, created a noticeable decline in morale and productivity. Having identified this blind spot, he compensated by removing the chairs from his office so that none of his team could come to meet with him. This tactic necessarily created a new intentionality, forcing Dan out of his office to engage with others—and he began to build meaningful relationships. Still shy by nature, he transformed himself into a walk-around leader with higher levels of engagement with his team. He became what my extra-extroverted wife affectionally calls me: “a high-functioning introvert.”

Another executive’s blind spot was a kind of “I know” attitude, valuing being right about everything. Like one of the “smartest guys in the room” that Enron made infamous, Mike was off-the-charts brilliant, well read, and overflowing with confidence. However, unlike the Enron men, he was coachable and, once made aware of his “omniscience complex,” wanted to show up differently for his people. He realized that his ability to solve almost any problem meant that he couldn’t envision anyone else who could. So, at his next team meeting, he agreed to do two things: (1) not sit at the head of the table, and (2) remain deliberately silent. When a problem emerged, everyone looked at Mike for an answer. With courage, he kept his promise and remained silent. It was awkward at first, but soon enough others started weighing in with their ideas, including some who had never really leaned in before. Within minutes, several viable solutions emerged. The team’s solutions were innovative and smart, some better than what Mike might have proposed. His “omniscience complex” had stifled discussion and inhibited the strength of the diversity of his team. In turn, his conscious abstention granted license to his team to think for themselves.

Sometimes leaders are aware but haven’t found the courage to act. After briefing Greg, the CEO of a multibillion-dollar oil and gas company, on the results of a 360-degree review, he conceded his dispassion and coolness, a lack of empathy that was causing him to fall woefully short. An engineer by training and a linear thinker, he argued he had no time to do “kumbaya.” “I know,” he admitted, “this has been my blind spot my whole career.” He tried the “practice makes permanent” principle: the more you do something, the more likely it is to become a habit. And once it becomes a habit, it is easier to maintain and can become transformational. “So you want me to fake empathy?” Greg asked me, arguing that the thing he disliked almost above anything else was a “phony.” “Sure,” I said, “let’s give it a try.” Greg began intentionally inquiring about the families and children of his team members. He took time to humbly inquire about people’s lives, even though it felt forced and unnatural to him. Over weeks of practicing the habit of what he called “forced empathy,” he became, over time, a more sensitive and compassionate leader with a much stronger followership.

Whatever it might be, every leader has a blind spot, a spot they cannot see that restricts their ability to navigate the road of leadership safely. While others around them can see it, most leaders are oblivious. They do not intend for their organizations to become dysfunctional or lose morale; it is simply and exactly a result of a lack of awareness of the impact of their own behavior. The advantage of learning to see what we have not previously seen in ourselves, and then courageously engaging with it, perhaps over a lifetime, is the secret sauce of what most great leaders have in common.

Common leadership blind spots

Dr. Tasha Eurich, an organizational psychologist and New York Times best-selling author of Insight: Why We’re Not as Self-Aware as We Think, discovered that 95% of people think they are self-aware, but only about 15% really are.12 That means that the vast majority of people lie to themselves about whether they are lying to themselves. This is, sadly, consistent with our own research on awareness, which suggests that only 13% of leaders are truly self-aware. The leaders we define as self-aware have strengths in four critical areas: reflectiveness, openness, inquisitiveness, and objectivity.13

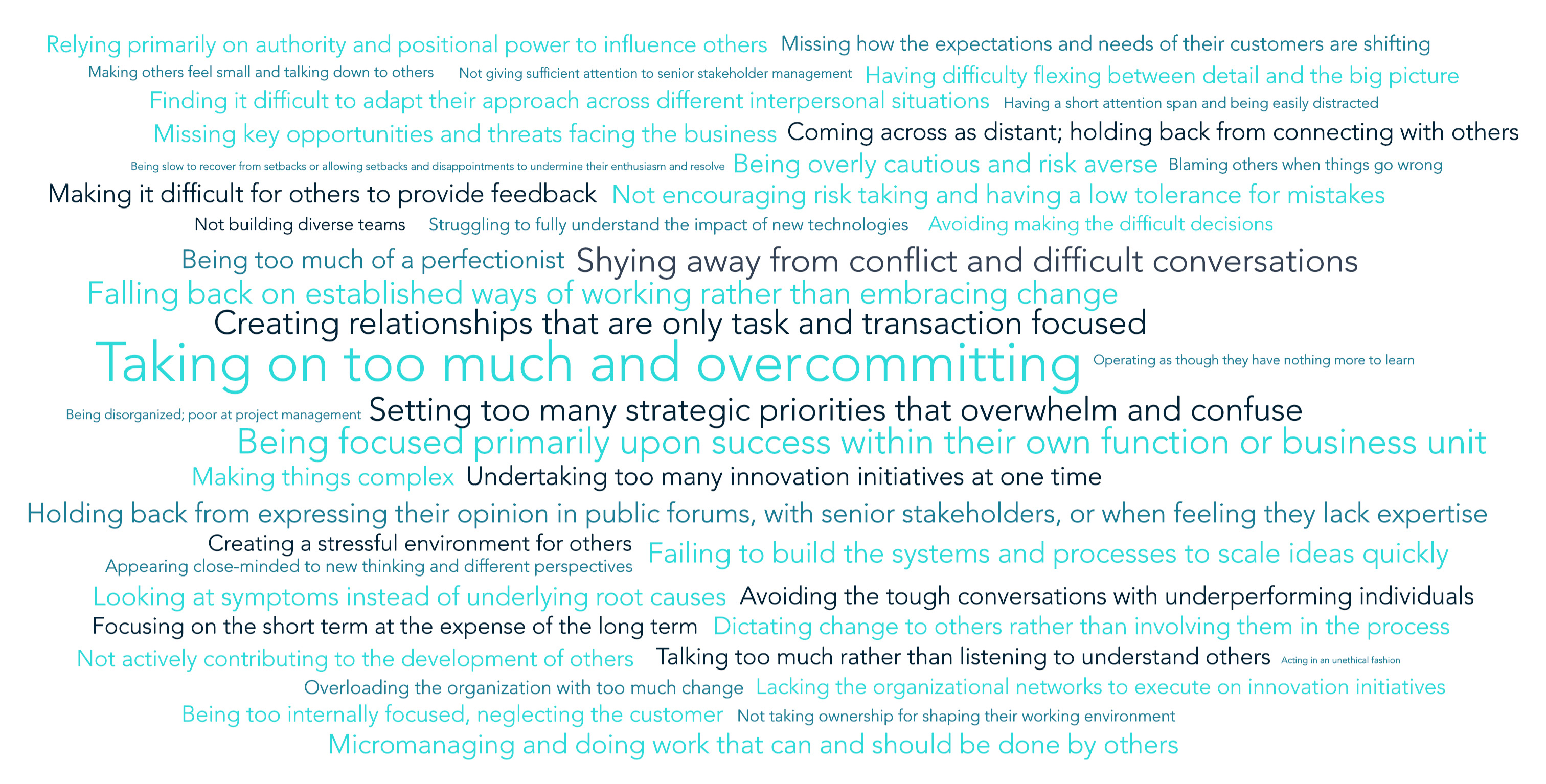

Our research doesn’t only highlight how rare self-awareness is; it also allows us to pinpoint specific strengths, development areas, and potential derailers for individual leaders, teams, and organizations. In the course of this work, we have identified 44 major blind spots that may cause derailment and, at times, destruction.14

Some of the most common blind spots result in leaders who are people pleasers, who must fight the temptation to be liked, avoid conflict, and appease others by daring to be braver and more direct. Some result in micromanagers or controlling leaders, who must learn to let go and experience the liberation of pushing authority down. Other leaders with blind spots have difficulty managing emotions and must learn to develop resiliency and self-control. Yet others are easily triggered and must learn how to manage frustration, disappointment, a bruised ego, or defeat. Then there are those who find it hard to provide structure; therefore, they must intentionally create boundaries and organizational systems. The easily distracted must learn to be more present and enable the golden rule of treating others with their full presence as they would wish to be treated.

Why blind spots remain elusive

As leaders develop, they are assessed frequently, and more and more often receive real-time feedback as well. Most of them want to show up better as leaders with their followers and peers—and even better humans in their personal relationships. How is it, then, that so many reach the most senior levels in bubbles, like Dick Fuld did? Why do so many of them still have such distorted self-perceptions and general unawareness of their own awareness?

First, the more senior leaders become, the less often they get honest feedback. Fuld may be an extreme example of this, but it is a well-known phenomenon that leaders become surrounded by people who tell them what they want to hear. Particularly in organizations that primarily reward short-term business performance and pay little attention to how leaders lead, many leaders have little incentive to examine their behavior or change it.15

Second, we all have defense mechanisms, and we believe that because our intentions are good, any negative impact we may see cannot be our fault. Many leaders then deflect blame, which makes blind spots even harder to see. Take, for example, an executive who was a potential CEO successor of a large pipeline company. When presented with the results of his 360-degree review report, this leader was stunned that he was perceived as “controlling” others. He then proceeded to spend the entire hour arguing about the data. “If the data were simply recut with different raters,” he implored, there would be no flaw of “micromanaging.” Sadly, he remained in the dark and was passed over for succession.

And there is a third, larger force at work today. In her book, Eurich argues that our increasingly self-centered or “me-focused” culture makes self-deception easier to fall into. “Recent generations have grown up in a world obsessed with self-esteem, constantly being reminded of their special qualities,” she writes. “And it is fiendishly difficult to examine objectively who we are and how we’re seen.”16

Social psychologist Dr. Jonathan Haidt highlights the “phone-based generation” in which, he argues, real relationships are neglected, self-esteem is magnified, and awareness has declined. The author of recent bestsellers such as The Anxious Generation and The Coddling of the American Mind, Haidt argues that the tendency to be constantly reminded of our special qualities and soothed by the dopamine from social media likes and mentions makes people more self-absorbed, which makes us less acquainted with our flaws and blind spots.17

Feedback is also increasingly sporadic in our family and personal relationships. There are fewer direct conversations and interventions, all in the name of being well-liked and “keeping the peace” in our increasingly divisive world. If we needed any evidence of the need for stronger feedback cultures across our society, consider the grassroots popularity of the “Dare to Lead” movement led by Dr. Brené Brown, whose seminars on the courage to have difficult conversations have filled basketball arenas.

All this is exacerbated by an epidemic of narcissism and entitlement, modeled by the highest-profile leaders and celebrities of our day. Narcissists’ failure to achieve intimacy with anyone can easily become more and more common in our virtual world of isolation. As cultural commentator Zoe Williams put it, we become narcissists when we see “other people like items in a vending machine, using them to service their own needs, never being able to acknowledge that others might have needs of their own, still less guess what they might be.”18

Taken together, all this creates a crisis we might call a “self-awareness deficit.” Leaders, reflective of our broader society, seem collectively less self-aware, unable to see that third face.19 Now, with more expected and more at stake for corporate leaders than ever before, we cannot afford such a huge, and growing, deficit. Knowing about our lack of self-awareness should catalyze the courage to change.

Seeing blind spots and exercising the courage to manage them

We can be leaders who are brave enough to confront our flaws and contend with them. We can be leaders, as Margaret Heffernan describes, “capable of a rich dialogue with themselves, who aren’t isolated by power, and for [whom] a sense of history delivers an enriched sense of the future.”20

Heffernan describes these people as the “Cassandras,” after the ancient Greek mythological royal whose prophecies came true—the one who was able to see what others could not. The Cassandras can see better because they “listen carefully to silence but don’t succumb to it ... and who clearly demonstrate that, while willful blindness may be part of the human condition, it need not define who we are.”21 All leaders can see themselves better, even rise to Cassandra-like Greek heroes, but only if they are purposeful about heightening their self-awareness and confronting the spots that obscure their vision.

Based on our extensive research, we know there are tangible ways to find blind spots in leadership once you have the courage to look. It starts with understanding that both internal and external awareness matter; the way you show up to others can help you understand what you’re not seeing in yourself.

External awareness

Externally, there are several proven formal tools, including soliciting feedback through 360-degree assessments or through the power of coaching, creating thinking partners, or forming your own personal board of advisors. Informally, feedback can be solicited by inquiring periodically of colleagues how you might have shown up better, for example, on a client call, presenting a business development pitch, leading a meeting, or managing a thorny or complex problem in a team meeting.

Our philosophy on developing leaders is that experiential development is far superior to classroom teaching. Research indicates that experiential learning accounts for approximately 70% of tangible development outcomes; relationships and feedback, or social learning, comprise 20%; and formal education and training contribute around 10%.22 In other words, leaders accelerate far more quickly in stretch assignments or rotations, or from assessments and 360-degree review feedback initiatives, than from reading a book or attending a seminar at an institution of higher learning.

Internal awareness

Internally, awareness is about seeing yourself clearly. Being curious and introspective are qualities related to self-awareness, as our research shows. These capabilities are enhanced by leveraging your inner humility, getting away from the noise of the world, and considering your emotional state or your aspirational dreams. You can do this with retreats, “think weeks,” sabbaticals, or, even better, setting aside some time each day to practice what the stoics or evangelicals call “quiet time.” It might also be as simple as a long walk.

There is certainly a time and a place for solitude for a leader, which can be precious, revelatory, and even transformational. One caution, however: in excess, an extreme self-absorption or apathy can develop. In this case, the cure becomes worse than the disease. Or, as Fyodor Dostoevsky cautioned, “the direct, lawful, and immediate fruit of consciousness is inertia—that is, a conscious sitting with folded arms.”23 Eurich’s research has found that people who introspected in excess were “more stressed, more depressed, less satisfied with their jobs and relationships” and had “less control of their lives,” which can lead to feeling trapped in “a mental hell of our own making.” Eurich also offers a way of compensating: to ask “what” questions (such as “What are my real motivations, capabilities, and strengths?” or “What is keeping me from becoming the best version of myself as a leader?”) instead of “why” questions (such as “Why is employee engagement at my company so low?” or “Why is my team so uncooperative?”), because “what” questions move us onward and upward, whereas “why” questions tend to spiral us out of control.

Seeing and naming blind spots, when done in a healthy way, should produce energy, hope, and the courage to change.

Conclusion

What most successful leaders have in common is a heightened self-awareness, to see what other leaders have not been able to. For leaders to ascend and shine for others, they must first descend with humility to a place and a time of reflection and self-understanding. It is a precious time when leaders increase their awareness quotient and start naming blind spots.

If self-awareness is the most powerful tool for transformation that a leader has, then combating and mastering a flaw with courage is the most powerful way to wield that tool. Each of us, from the time we are born and through adulthood, is engaged in the project of building our character—sometimes it is new construction, and other times, a renovation project. Either way, we are built by nails, board by board, with sharp awareness and precisely wielded courage.24

It is this heightened consciousness that holds you to a higher standard of knowing who you are and leading others well. You may begin to take yourself less seriously and consider others more carefully. You may discover your third face, warts and all. It gives you a renewed courage to show up as your more authentic version of yourself, with an informed and engaged conscience that allows your potential to soar. And it almost always produces the wings of freedom and unleashes the power of humility. Or as philosopher G. K. Chesterton said, “Angels can fly because they can take themselves lightly.”

Acknowledgments

I would like to say special thanks to my colleagues from our Heidrick Digital Labs team who were instrumental in interpreting the data and adding valuable insights to this piece. They include Dr. Karen West, partner and head of psychology, Product Research & Design, Heidrick Digital Labs; and Dr. Kate Malter McLean, director of psychology, Product Research & Design, Heidrick Digital Labs. I am also grateful to Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase, for sharing his insights; and to my Heidrick & Struggles colleagues David Peck, who leads our Coaching services, for his contributions on “blind spot maintenance,” and Josselyn Simpson, vice president, global editorial director, for her good literary counsel. And, of course, I am always thankful to my team, Ali Van Norman, senior associate, and Claire Deaust, executive assistant, for their support and always helping me to see what I don’t see.

About the author

Les Csorba (lcsorba@heidrick.com) is a partner in Heidrick & Struggles’ Houston office and a member of the CEO & Board of Directors Practice. He is the author of Trust: The One Thing That Makes or Breaks a Leader.

References

1 Stephen Foley, “Crash of a titan: The inside story of the fall of Lehman Brothers,” quoting an interview with Larry McDonald, Independent, September 7, 2009.

2 "Ex-Insider's book details Lehman Brothers collapse," NPR, July 21, 2009.

3 Renae Merle, “A guide to the financial crisis—10 years later,” Washington Post, citing data from Moody’s Analytics, September 10, 2018.

4 Dick Heller, "Leadership is needed now for America to have a viable economic future," Huffpost, March 18, 2010.

5 Margaret Heffernan, “Three problems of power,” Medium, January 12, 2021, medium.com.

6 Stephen Foley, “Crash of a titan: The inside story of the fall of Lehman Brothers,” quoting an interview with Larry McDonald, Independent, September 7, 2009.

7 Statement of Richard S. Fuld, Jr. before the United States House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, October 6, 2008, p. 2.

8 Maureen Farrell and Stephanie Yang, "Lehman’s Fuld, 7 years later, says ‘perfect storm’ caused crisis," Wall Street Journal, May 28, 2015.

9 Edgar H. Schein, Humble Inquiry, The Gentle Art of Asking Instead of Telling, San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2013.

10 Bill Murphy Jr., “With 11 short words, Elon Musk just showed a tiny glimpse of self-awareness and humility,” Inc., June 15, 2019.

11 Ruth Umoh, “Warren Buffett calls this trait his ‘clear weak point,’” CNBC, June 29, 2018.

12 Tasha Eurich, Insight: Why We’re Not as Self-Aware as We Think, and How Seeing Ourselves Clearly Helps Us Succeed at Work and in Life, New York: Crown Business, 2017.

13 Proprietary analysis of assessments of 2,268 executives, conducted between February 14, 2024, and June 2, 2024.

14 The analysis is now based on assessments of more than 75,000 leaders and 3,500 teams. For more on our META (mobilize, execute, and transform with agility) framework for leadership and our ongoing work and research, see Steven Krupp, “Putting META into action,” Heidrick & Struggles.

15 For example, see James Heskett, “As leaders, why do we continue to reward A, while hoping for B?” Harvard Business School Working Knowledge, August 1, 2023.

16 Tasha Eurich, Insight: Why We’re Not as Self-Aware as We Think, and How Seeing Ourselves Clearly Helps Us Succeed at Work and in Life, New York: Crown Business, 2017.

17 Jonathan Haidt, The Anxious Generation, New York: Penguin Press, 2024; and The Coddling of the American Mind, New York: Penguin Press, 2019.

18 Zoe Williams, “Me! Me! Me! Are we living through a narcissism epidemic?” Guardian, March 2, 2016, theguardian.com.

19 The phenomenon of people becoming less proficient in assessing themselves accurately overall, not just being blind to flaws, is called the “Dunning-Kruger effect.” Most often this is defined as people who overestimate their abilities, and so have what is called an “illusory superiority,” though it can also lead to people underestimating their strengths. See Eric C. Gaze and The Conversation US, “The Dunning-Kruger Effect isn’t what you think it is,” Scientific American, May 23, 2023.

20 Margaret Heffernan, Willful Blindness, New York: Bloomsbury, 2011, p. 222.

21 Margaret Heffernan, Willful Blindness, New York: Bloomsbury, 2011, p. 201

22 See, for example, “Learning in the digital age,” EFMD Global, efmdglobal.org.

23 Fyodor Dostoevsky, Notes from Underground, 1864.

24 Tasha Eurich, Insight: Why We’re Not as Self-Aware as We Think, and How Seeing Ourselves Clearly Helps Us Succeed at Work and in Life, New York: Crown Business, 2017.